A tribute to Coleen Seng

Brent Lucke on the legacy of Lincoln's former mayor.

Hi,

Today we've got a first for this newsletter: An essay from a guest writer!

Brent Lucke is a community organizer with a vast knowledge of Lincoln history. He's the one who first introduced me to Roger Welsch's book Inside Lincoln, which I wrote about earlier this year. And he kindly agreed to write a piece about former Lincoln mayor Coleen Seng, who died on Dec. 1. It's not an obituary per se; it's more of a personal reflection from Brent about Seng's legacy as a neighborhood organizer and the small ways in which their lives intersected and overlapped.

I learned a lot about Seng from reading Brent's essay, though he didn't actually touch on my favorite anecdote about the former mayor: The time back in 2004 that she tried to collect $31,900 from Dick Cheney, after the then-vice president forced Lincoln to spend that amount on security during a visit to the city for a political fundraiser. (Cheney, who was raised in Lincoln, took an unplanned detour to visit his childhood home, which seemingly contributed to the high cost.)

A Journal Star editorial at the time blasted Seng for the move, arguing that it made Lincoln seem "petty and inhospitable," and local Republicans decried it as a partisan stunt. I think there's a more charitable reading — one more in line with the portrait of Seng that Brent sketches below — which is that she cared deeply for Lincoln and didn't want local resources squandered on political theater that didn't benefit the city. But maybe it's a moot point, as it doesn't seem like Seng ever managed to actually recoup those costs (or at least, I couldn't find any evidence that she succeeded).

Still I think we can say that Seng — a woman who devoted her life to making her adopted city a better place — at least left behind a better legacy than the man who orchestrated America's War on Terror. So maybe she really did win out in the end.

Thanks, as always, for reading. Send feedback, good or bad, to tynanstewart@proton.me

~ Ty

If you'd like to help me pay people like Brent to write cool things about Lincoln, please consider signing up for a paid subscription. It helps a lot!

A tribute to Coleen Seng

by Brent Lucke

Coleen Seng always showed up.

I didn’t really know Seng, the former Lincoln mayor and neighborhood organizer, who died earlier this month at the age of 89. I did, however, have the privilege to interview her once, and I remember hoping — as I waved goodbye to her daughter and let the storm door of her house shut behind me — that I left a good impression.

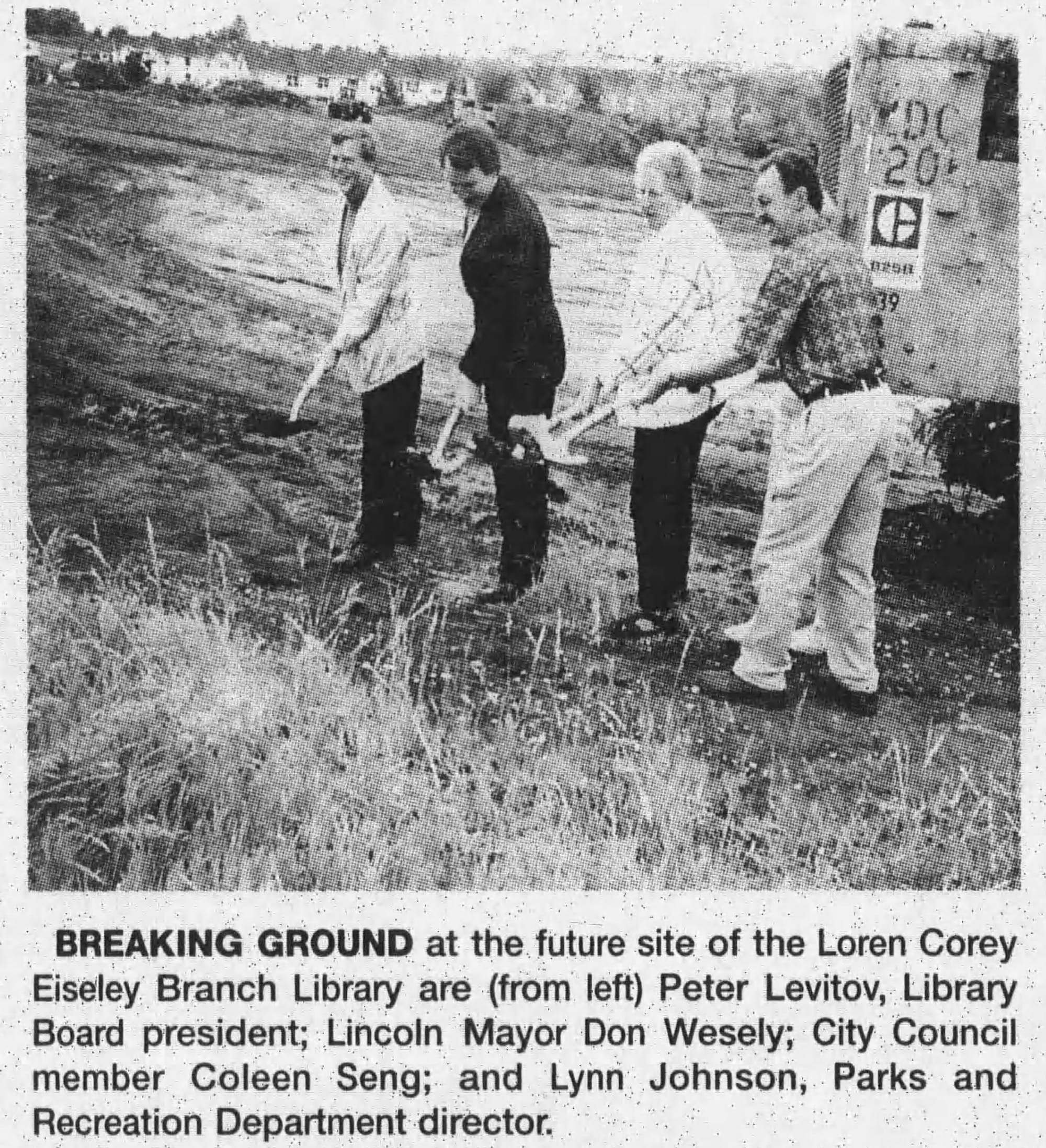

That said, I do know about Seng’s life works and the relationships she helped build in her beloved University Place neighborhood and across the city we know and love. I know that she was a builder of consensus, a competent weaver of the vibrant quilt that is Northeast Lincoln. I know that, as mayor, she always kept a pair of boots in her car, so that bad weather would never keep her from a groundbreaking or community event. I think that speaks volumes to what, and who, she valued when she had a position of authority.

This isn’t an obituary; as I said, I didn’t know her that well. But I find the story of her life both personally affirming and inspiring. Not many people in Lincoln’s history can claim to have given so much of themselves to this city, and few, whether born here or not, have become so important to the soul of this place.

Seng wasn’t a native of University Place or even of Lincoln. She was born in Council Bluffs — and, as someone also born in Iowa, I hope you’ll forgive her for this transgression. She grew up in Fremont and finally arrived here as an undergraduate at Nebraska Wesleyan University during the Plainsman era (if you know, you know) of the 1950s. Some of us, myself included, often find ourselves grumbling at “college kids,” especially when they come close to mowing us down on an O Street crosswalk as they careen toward a Friday night rager. But while many students depart after obtaining their degrees, having done little for the city besides contributing to traffic and treating service workers poorly, Seng didn’t leave — or didn’t for long.

After graduation, she left Lincoln briefly to work for the Girl Scouts of America. However, both her future husband and (I like to think) University Place called her home when a serendipitous opportunity to continue her work with the Girl Scouts in Lincoln materialized. That chapter of her career was short though, and she soon began the work that would grow to become her legacy, thanks to the ministry of Ebb Munden at University Place’s First United Methodist.

Having arrived in Lincoln by way of New Orleans, Munden brought with him lessons — rules for radicals, one might say — that had proved effective in his old congregation: The teachings of Saul Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation, a foundation that trained religious and civic organizations to build networks of solidarity for the purposes including community preservation. First United Methodist hired Seng for a job to assist with organizing the University Place community in service of combating material decline and cultivating the people power necessary to enact systematic change, a role that’s sadly harder to imagine any single congregation having the capacity to support today. Alongside her neighbors and the faculty of Nebraska Wesleyan — two groups which were, back then, often one and the same — Seng started building the neighborhood association that would come to represent the area: the University Place Community Organization.

UPCO, as it came to be called, started its efforts by investing in the community’s urban canopy and neighborhood clean-ups. In partnership with emerging neighborhood associations in the Near South, Clinton, and Malone, UPCO also sent a delegation, including Seng, to train at the Industrial Areas Foundation in the mid-1970s. Ultimately this training and cooperation culminated in the formation of the Lincoln Alliance.

I could (and will eventually) write a much longer piece on the Lincoln Alliance and both its accomplishments and downfall. However, just as this isn’t an obituary, it’s also not an essay on local organizing history, though more of those are certainly needed in Lincoln. For now, I’ll say this: The Alliance, under the leadership of faith, community, and emerging political leaders of the era, including Seng, famously killed a proposed urban freeway that would have torn through the fabric of Northeast Lincoln and fought against red-lining, street widening, and public disinvestment in core neighborhoods.

The Alliance also challenged the concentrated wealth and power of South Lincoln, winning a reform to the way we elect City Council members and creating a pathway that would lead Seng to a life of public service at City Hall. Prior to 1979 the whole council was elected at-large — meaning the entire city would vote for every candidate. It took money and political infrastructure to get in office, barring many “normal” Lincolnites from seeing themselves in office. But in 1978 a ballot measure created council districts, including one for Northeast Lincoln.

Seng was elected to that seat in 1987 and served as the area’s representative for 16 years. She became known for her ability to build consensus in a section of town with neighborhoods rooted in both pours and pulpits: Balancing the once rival communities of pious University Place and roughneck Havelock alone is a feat. She was later elected Lincoln’s 50th mayor on May 6, 2003, and while her single term wasn’t what I believe she or her supporters hoped it could be, I don’t doubt her dedication to this place and us who call it home.

It was a typically windy day in June of this year. As the pack of 30 or so cyclists crossed Adams Street — in small groups as the traffic intersecting the Dietrich allowed — I thought about Seng.

She chose Lincoln as the place to spend the rest of her life, in part because she fell in love here, but also because she fell in love with here. As far as I can tell from our one meeting, Seng grew so closely linked with University Place that she could never bring herself to leave it, even decades after her husband’s passing.

One need not be born in a place to care for it deeply. In fact, I would argue that it is this “found” aspect of our towns and neighborhoods in Nebraska that allows transplants to feel an attachment to our communities greater than the urbanites of the coast or suburbanites and acreage dwellers of western tax havens. A beloved home of circumstance is, to my mind, the only spiritual equal to the hometown that so many Midwesterners idealize (those who found belonging where they grew up, that is).

I found a stopping place in the northwestern corner of UPCO park. The group parked their bikes, and, with a script in my hand, I switched on the little portable speaker strapped precariously to my backpack and prepared to tell the crowd about the Lincoln Alliance’s victory over the proposed highway, how Seng and her neighbors in UPCO rose to the occasion, working alongside their brothers (and sisters) at-arms in Clinton and Malone to save and reinvest in them.

I regretted that I hadn’t invited Seng on this tour, which had been organized in honor of one of her battles as a community organizer. But I was proud to be amongst the storytellers and torchbearers following in her footsteps. I know her spirit and her legacy will continue to touch Lincolnites, wherever neighbors gather with open hearts and hands ready to lift each other up.

Brent Lucke is proud Lincolnite, Hawley Hamleteer, and community organizer living in the Malone Neighborhood with his wonderful fiancé Haley and their opinionated cat Nellie. A Tri-Cities kid from Grand Island, he serendipitously fell in love with Lincoln after attending UNL for his undergraduate degree – developing a fixation of the life works of Roger Welsch, prairie architecture, and local history. This essay is being co-published in his newsletter.